It seems strange nowadays, in this world of a “healthy tan’ that pale skin was once so much admired. Like so many things in fashion, it comes from a statement of affluence, and status. In times gone by, the poor usually worked out of doors, and had a tanned face, hands and arms whether they liked it or not, so a pale skin was a sign of wealth and high class. To be pale meant you didn’t have to work for your living. Ladies who had to go outside in the sun, for example to a garden party, would carry a parasol, and make sure they wore shady hats and high necked dresses, to keep the face and neck as white as possible, and avoid the dreaded freckles.

However as industry began to move indoors, pale skin started to be associated with poverty, especially when foreign travel, always the preserve of the rich, became more widely available. To have a glowing tan showed that you could afford to travel to exotic locations. Tanning salons arrived, to provide artificial tans and suggest that the tanned person had enough money to travel to expensive destinations.

These salons have brought serious health risks with them, as has prolonged natural tanning. In particular, over-exposure to sunlight causes cancer. A melanoma sounds fairly innocuous as it is a form of skin cancer but it can spread to other organs, and cause death. There even seems to be a form of mental addiction to tanning – called tanorexia – where sufferers are incapable of stopping using tanning salons, and seriously harm their health in the process.

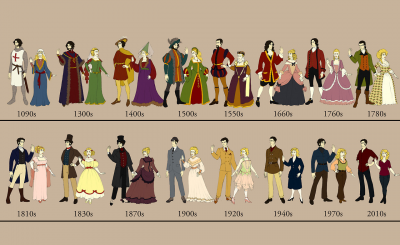

At quite the other extreme, before a tan became fashionable, make-up was used to heighten the pale complexion, especially during Elizabethan times. This was far more prevalent than tanorexia is nowadays and was deadly. The make-up used to make a skin look very pale was called ceruse and contained what we now know are serious poisons. The ideal “look” for a high-class Elizabethan lady was dead white skin (including the neck and bosom), narrow, highly arched eyebrows and high forehead, bright eyes, a very red mouth, and reddish or blonde hair. Elizabeth herself set the fashion, and had naturally reddish blonde hair. Her cousin, Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester, was also considered to be a great beauty of the time, and these two women set the trend that others followed.

The dead white skin showed off wealth, and status and was copied by men as well. In women it was also supposed to show that they were dainty and fragile. Ceruse was a mixture of white lead, and vinegar, mixed to a paste, and applied very thickly. Sometimes Alum was used instead of white lead, which is less poisonous, but still not very safe. And a “glaze’ of egg white could be applied afterwards to “set’ the ceruse and disguise wrinkles.

Skin problems were much more common than nowadays, and smallpox was still a common disease, so the very thick make-up was seen as necessary to hide the blemishes and “fill the holes’ – rather like plastering a wall. Totally unblemished skin was very rare.

Even at the time, it was noticed that this terrible concoction didn’t seem to do the skin any good, and in fact made it worse, so that the wearer needed more and more of it to cover up the mess. Skin went grey under the ceruse and became shrivelled, making the wearer look prematurely old. The fact that it was also poisonous was known at the time. But people carried on using it. In fact, they even used Mercury as a face-wash! Mercury was used in medicines and the fact that most people taking the treatment seemed to die wasn’t commented on at first.

Eyebrows were plucked very thin and arched, as was the hairline to give that essential high forehead. If you wanted paler hair, the best bleach available to you was urine. It does act as a bleach, although the smell is unfortunate. However, seeing as Elizabeth herself, who was considered to be over-hygienic, only bathed once a month, maybe they didn’t notice. The Court must have been a very smelly place.

To achieve the vital bright-eyed look, drops of Belladonna were put into the eyes. Belladonna is still a listed poison (as is white lead and mercury), and can easily kill.

Finally, the red lips were achieved by various mixtures, some fairly safe, which included such ingredients as cochineal (crushed beetles, still used as food colouring), and madder (a natural dye-stuff). But the favourite was vermilion (mercuric sulphide), which is toxic. The eyes were lined with kohl, made from powdered antimony – another toxic substance. It was noted at the time that a painter didn’t need any paints – he could just use the nearest lady’s face as his palette!

During the Regency period, women’s clothing was very influenced by the Grecian period and clothes were very lightweight and made to look like flowing robes which clung to the body. They were made of sheer fabrics such as muslin and to make them cling to the body it wasn’t unusual for the fabric to be dampened. This practice was certainly unhealthy, although it probably wouldn’t have mattered in Greece as the weather is so much hotter. But in a temperate climate like the UK, despite the fact that the late 1700s were unusually warm, lightweight, damp clothing could not possibly be called healthy. This fashion later gave way to the Empire line dress which is what Jane Austen’s heroines would have worn, and which was an adaptation of the earlier Grecian inspired clothing.

One fashion feature that has preoccupied the fashion-conscious since very early days is body shape. Even today, when the fashion is to be unnaturally thin, crazy diets, major surgery and strange “treatments’ are tried out, and anorexia, an extreme form of dieting resulting from a mental condition, has killed hundreds, and destroyed the health of countless others. At different points in time, different shapes have been favoured, and a common way to alter one’s shape was to wear a corset.

Corsets have a long history and were available for men as well as women. Essentially, they are a splint, made from heavy fabrics, and stiffened with all manner of different things from whalebone to wood and even steel. They could then be drawn tighter by laces. What the corset did to the human body depended of course on the desired shape. At their most extreme, they were pinched in the waist – for example during the 1830s and again later in the nineteenth century, – to a highly unnatural degree. Regardless of the natural shape of size of the woman, an 18 inch (46 cm) waist was seen as ideal. The idea was that a man could encircle a woman’s waist with this hands, so that his middle fingers and thumbs would touch around her.

This shape was so highly sought after that girls were introduced to corsets at a very early age – I have seen a corset made for a one year old girl. The girl then “grew’ into the tight-waisted woman, rarely out of a corset. The result was indeed a narrow waist, but the medical impact was enormous. The internal organs were unable to grow in their natural position and in some cases – particularly the liver – were almost cut in half. The lungs could not form properly, and it is no surprise that Victorian ladies “swooned’ so frequently, as they literally could not get enough oxygen. It would be commented on that Lady Such-And-Such had a “bird-like’ appetite, but the truth was that eating was rather difficult. A friend of mine attended a Victorian banquet as a Living History exercise, and laced into her corset found she could hardly get any food down her throat, despite being ravenous!

Some women wore corsets for so much of the time, and had them laced so tightly, that taking them off became dangerous, as they hadn’t built up enough muscle strength in their backs to support the top half of their body unaided.

During the Edwardian period, the fashionable shape was the S-bend, which required the corset to push the top half of the body forwards, and the bottom half backwards, which created a swan-neck effect that was highly desirable. But the corset of course was agony to wear as this is such an unnatural position. And just when you thought it couldn’t get any more extreme, the Hobble-Skirt came into fashion. This was a dress that was so narrow that taking ordinary steps was impossible, and the corset was lengthened to help the wearer take the tiny steps necessary. Some women even tied their ankles loosely together to help take the short steps. But the real difficulty with the longer length corset was that the wearer could not sit down!

Men too had their difficulties, and corsets for men were worn from early eras, usually to hold in the stomach, and create a more slim-line shape. During the Regency, men’s calves came into prominence, and false calves, made of cork, were worn down the back of men’s stockings, to create the shapely look.

There were various attempts during the Victorian era to protest against the extreme restrictions, and health hazards of corsets, principally the Dress Reformists, but fashion usually won out over these campaigns. Corsets were designed for children, and even pregnant women, and these sold well, despite several well known scientists protesting against the health dangers.

There have been several high-profile accidents or deaths from fashion – for example, Baby Spice’s ankle injury from platform shoes, or Isadora Duncan’s death when her long flowing scarf became entangled in the wheel of a car – but until modern times, the second highest cause of premature death amongst adult women (after childbirth) was due to their clothing. Long skirts and open fires simply don’t mix.